COVID-19 & The Spectres of Quarantine for the Chinese Canadian Community

Written by Angie Wong, PhD

Contract Lecturer, Women Studies, English, and Indigenous Learning,

Lakehead University

(The Asianadian, vol. 2, no. 4. Cover Image courtesy of The Asianadian Co-founder, Cheuk Kwan)

The crisis of COVID-19 has ushered in a new ‘normal’ for Canadians. Handshaking is now a dangerous proposition. Masks are being donned on the streets of Canadian cities, and it is not only Asian Canadians wearing them. Indeed, the entire world is now being forced to adopt some of the very symbols and practices that previously marked Asian Canadians as different (even suspect). But rather than creating a larger feeling of solidarity or common struggle between Chinese and other Canadians, the crisis of COVID-19 has once again made it scary to be Chinese in Canada, and North America more broadly. The coronavirus is a disease that has been racialized as the “Chinese virus,” loudly echoing the Orientalist notion of the Yellow Peril and the racist idea that ‘China is the sick man of Asia’. Of course, this is hardly the first time that Chinese people have been feared in Canada.

“But rather than creating a larger feeling of solidarity or common struggle between Chinese and other Canadians, the crisis of COVID-19 has once again made it scary to be Chinese in Canada, and North America more broadly. ”

(The Asianadian, vol. 2, no. 4. “A ‘Prison for Chinese Immigrants” by Chuen-Yan David Lai. Image courtesy of The Asianadian Co-founder, Cheuk Kwan)

In 1908, the federal government erected an immigration building in Victoria, BC and designated it as a Detention Hospital for which mostly Chinese immigrants were detained when they first arrived in Canada (Lai 17). As Chuen-Yan David Lai discussed in a 1979 issue of The Asianadian: An Asian Canadian Magazine,the purposes of this immigration building, like others erected in Vancouver at the time was to process migrants, conduct head tax transactions, and question their route of arrival. Most of the Chinese men who came as labourers also underwent medical examinations, which resulted in them put into quarantine cells. As Lai recalls “the Immigration Building was notoriously known to the Chinese as Chu-tsai-uk (pigpen)” (17). This was among the first humiliations felt by the men who went through the ‘pigpen’. Many left their villages and were in Canada for the first time and without knowledge of the English language; most could not understand why they were incarcerated. Indeed, the Chinese immigration building was a carceral space used to determine which foreign bodies met the public health standards of a white, settler nation. Lai notes “although they may not have been physically abused, many must have been shaken psychologically by the incarceration experience” (Lai 19). We remain shaken.

The Writing on the Wall:

The two-storey immigration building was surrounded by walls and iron bars. The building was constructed like a dungeon, made with “five columns of red bricks and measured slightly over twenty inches thick…it is unnecessary for an immigration building to have such thick, exterior walls unless it is used for special purposes such as a prison” (Lai 16). Indeed, this was no ordinary immigration building. Thick, wrought iron bars encased every staircase, corridor, and fire exit and iron bars secured the windows. A windowless and uninviting reception area led to a large dining hall. The second floor contained the thick-walled prison cells for newly landed Chinese immigrants (16-7).

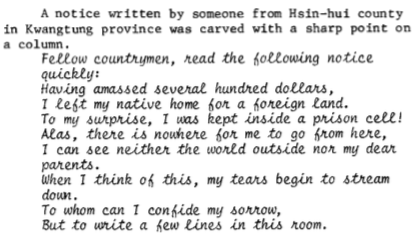

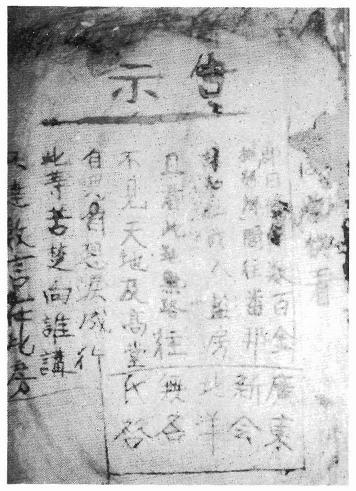

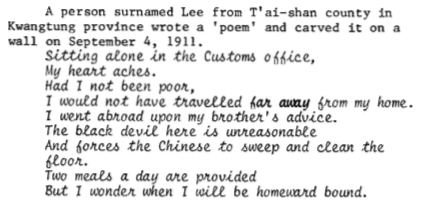

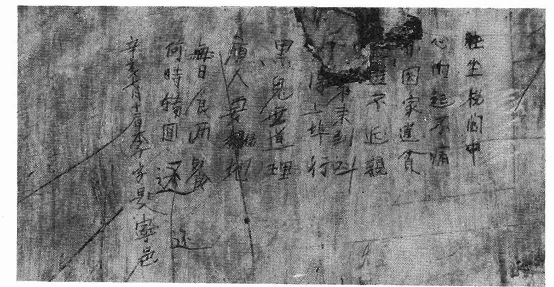

In their times of isolation and solitude, some Chinese men found solace by writing poetry on their cell walls. Though the immigration building of Victoria was demolished in 1977, these words of wisdom have survived and still offer us much. Lai provided photographs of the Chinese poems with his publication in The Asianadian’s 1979 Spring issue. Though they are haunting, they are also loving in their incredibly human sentiments of loneliness, a longing for home, and the pain of isolation.These writings on the wall reveal grit and resilience across time and space of the Chinese in Canada, yet they also capture the disappointments of Gold Mountain. To get a sense of what some of these men felt, Lai freely translated some of the following poems.

The Contagious Divide* & ‘The Sick Man of Asia’

The Yellow Peril is a historical form of xenophobia that marks East Asian people as a conquering mass that threatens western civilization and is most immediately a threat to the ‘white’ nation, ‘our’ jobs and ‘our’ economy. The immigration building discussed by Lai allowed immigration officers of Canada to mitigate the Yellow Peril by subjecting Chinese men to Western standards of public health and civility classifications. In the immigration building, state bureaucracy conflated Chinese bodies with the notion of ‘China as the sick man of Asia’—a sorrowful expression used to capture China’s internal and external conflicts with imperialism throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. The immigration building was the barrier that functioned to prevent sick Chinamen from entering into a civil, sanitized Canada. It was the first disciplinary space in which Chinese bodies were taught to act in accordance with white Canadian standards. The irony here, of course, is the extent to which these very standards of Canadian public health have now shifted.

Future Shock from Immigration History

Though our response to COVID-19 has been a collected, celebrated, and even boastful effort to practice social distancing protocols, it is nevertheless considered a utilitarian choice for the better health of all Canadians. A similar choice was made by the people of Wuhan, Hubei under the orders of the Communist Party of China. Choice and the notion of ‘choosing’ as an enactment of liberal individualism in western democracies underlies our decisions to follow social distancing protocols outlined by our governments. It was also the choice of the people of Wuhan to lockdown—though many in the West considered this to be yet another CPC infringement upon freedom and human rights, ignoring the fact that the people of Wuhan also suffered a great deal of stress and anxiety under the sudden lockdown order.

Yet, North Americans now find themselves adopting or being advised to adopt certain public health measures that were once deemed markers of foreign illness and CPC totalitarianism. For instance, wearing face masks is a practice that has been in use for decades in many Asian countries; recently, it has been quite skeptically adopted by Canadians due to fears of virus transmission. So, why the sudden rise in episodes of overt and violent anti-Chinese racism in both Canada and the USA? Because it is easier to blame Chinese people (or the CPC) than the slow neoliberal gutting of Canadian healthcare or the apathy to wealth disparities. It is easier to do as Canadians have always done: blame the Chinese, while demanding cheap labour and offer terrible living/working conditions at the same time. Yet, we ought to be a lot more concerned about transforming our social relations and habits than the corporate greed that has so many of us chasing toilet paper and hand sanitizer.

Continued neoliberal consumption may be the immediate response to ‘future shock’—what Alvin Toffler defines as our “limited ability to absorb the physiological and mental punishment inherent in change” (642). “Time is compressed” and the speed with which our social, economic, and political spheres move is rapid, which constitutes a collective human exhaustion (with one another, with other beings, with accountability). The constant need to supply and produce engenders a particularly tiring way of being that demands productivity or guilt (and the breakdown of bodies along with it), making self-reflection and the consideration of others appear unproductive, unmanageable, and useless compared to individual productivity. This means that our attendance to the past is not prioritized as a critical tool of reflection, which is why future shock is so shocking.

So, while we are in a moment of future shock with the uncertainty of this new global pandemic, we ought also to realize that this future shock should not come as surprise as it in intimately linked to the historical control of Chinese bodies under the guise of public health. This future is not shocking to Chinese in North America who have experienced and understand the experiences of anti-Chinese racism. Though the villainization and Othering of the Chinese for their food and hygiene differences remains, non-Chinese are quickly learning to adopt particular health practices that have been in use for decades (if not centuries) in Asia. This demonstrates a willingness to see beyond neoliberal reform. Yet, as we come to new realizations and appreciations that there are other ways of being in the world with which we can be reliant upon, there should also come the understanding that any returns to normalcy are attempts to ignore the wisdoms of the past and potentials of the future.

“So, while we are in a moment of future shock with the uncertainty of this new global pandemic, we ought also to realize that this future shock should not come as surprise as it in intimately linked to the historical control of Chinese bodies under the guise of public health. This future is not shocking to Chinese in North America who have experienced and understand the experiences of anti-Chinese racism.”

Works Cited

Lai, David Chuen-Yan. “A ‘Prison’ for Chinese Immigrants” The Asianadian, vol. 2, no. 4. 1979: 16-19.

Shah, Nayan. Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown. University of California Press, 2001.

Toffler, Alvin. “Future Shock” Classics of Western Thought: The Twentieth Century. Edited by Donald S. Gochberg. Wadsworth, 2004: 640-660.

*This concept is coined in Shah, Nayan. Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown. University of California Press, 2001.