Flower Numbers 花碼字: A Chinese Counting Legacy 中國數字之小歷史

English & Chinese: the Fête Chinoise Editorial Team

as seen in Edition 4 of Fête Chinoise Magazine

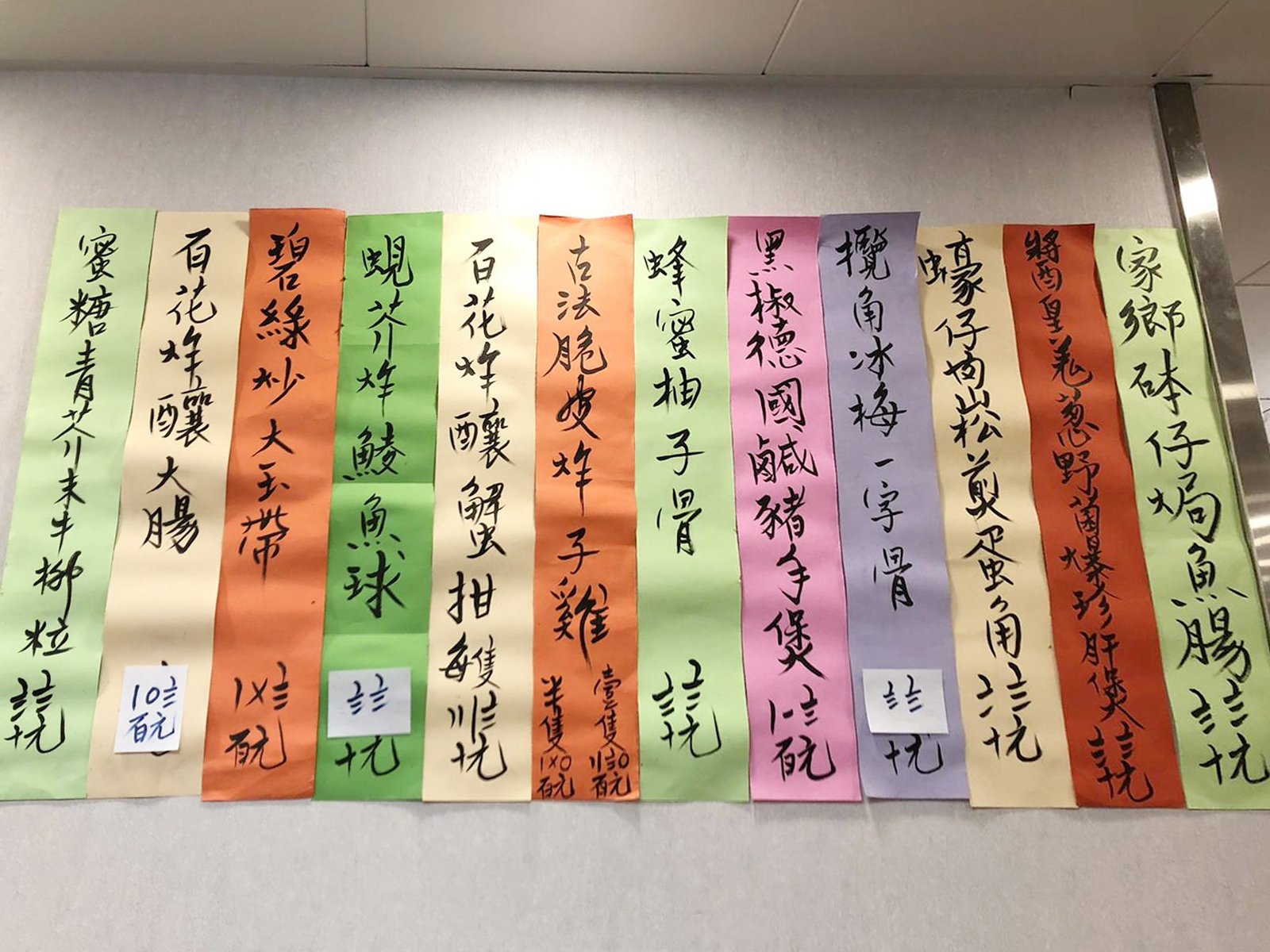

A menu with prices in Suzhou numerals at Lin Heung Kui restaurant.

Photography: Lin Heung Kui

Prices in the photo (left to right): $88, $108, $148, $88, $38, $140(half)/$280(whole), $88, $118, $88, $78, $88, $88

photography: Yale-China Chinese Language Centre (Twitter @CLC CUHK)

What are these symbols?

Known as “flower numbers” or “Suzhou numbers”, these symbols were once used in commerce, appearing on coins and later on fare signs in Chinese shops. These symbols are now a language of a legacy almost lost. Today, banks in East Asia still use flower numbers on cheques to help detect fraud, but other than that, they are only found in certain parts (e.g. on handwritten signs in marketplaces, on minibus pricing charts and invoices) of Hong Kong, where many no longer recognize them.

Suzhou numerals on banquet invoices issued by restaurants circa 1910–1920s.

Photo reposted from wikipedia (uploader: Mk2010)

這些符號是什麼?

被稱為“花碼字”或“蘇州碼字”,這些符號是一種快失傳的語言。它們曾經用於硬幣上,後來在商店裡的票價標誌也能看到它們的蹤跡。現在,東亞區的銀行在支票上還會使用這些花碼字來預防銀行詐騙。除此之外,它們就只在香港的小角落才被運用到,而很多香港人也不會看花碼字了。

sponsored by HKETO

But where did these symbols come from?

Many believe flower numbers represent the beads of an abacus. In 1883, when the late Professor Terrien de Lacouperie studied these numbers, he was adamantly trying to prove that the abacus was not native to Chinese culture.

He stated that the symbols for 6 (〦), 7 (〧), and 8 (〨) echo the abacus’ design where “the upper bead is worth five” (17) and the additional beads are added thereafter, much like the Roman numerals for 6 (VI), 7 (VII), and 8 (VIII). This connection revealed the possible relationship between the way people counted on an abacus and the way they recorded numbers in China at the time. Like Roman numerals, this shorthand was later superseded by the use of Arabic numbers.

photography: SCMP

In the early years of Jingzhang Railway, kilometer stones used Suzhou numerals.

Photography: N509FZ of wiki

花碼字與算盤的緣分

photography: James Yip (the loop hk)

許多人認為花碼字代表算盤中的珠子。1883年,Terrien de Lacouperie 教授在大英博物館編制中國硬幣目錄時研究過這些獨特的數字。他試圖用花碼字來證明算盤不是中國文化的原創物。他指出,6(〦)、7(〧)、和8(〨)的花碼字與算盤是互相呼應的。其中,花碼字直線代表算盤上方價值5的小珠(17),類似於6、7和8的羅馬數字利用的 V 代表5。原來,早期的中國文化數字跟著用算盤的方式有著很親密的關係。

Photo reposted from getit01

How long have these symbols been used for?

Flower numbers have been around for almost 500 years, first appearing at the end of the sixteenth century. Since these numerical symbols are only five hundred years old, and since there is evidence to show other countries have used the abacus long before then, the abacus was likely imported into China right before the sixteenth century. Professor de Lacouperie uses these symbols to prove that the abacus was a new counting tool to the Chinese, contrary to popular belief that the abacus is a native Chinese invention. To us, however, his research gives context to the legacy of flower numbers that only a small population of people now appreciate and understand.

Photo reposted from getit01

五百年的歷史

這些花碼字已經有五百年的歷史。它最初出現在十六世紀末。由於這些跟算盤相關的數字只有五百年歷史,de Lacouperie 教授覺得算盤很可能在十六世紀之前進口到中國。de Lacouperie 教授使用這些符號來證明算盤在明清時期還是一種新的計數工具。他發現雖然大眾認為算盤是中國本土發明,但是這個想法是沒有根據的。然而,對我們來說,這位教授的研究為我們解開了花碼字的來龍去脈 — 就算現在越來越小人懂得欣賞和理解花碼字。

PHotography: Shizhao of wiki

SPonsored by HKETO

The 2026 Lunar New Year celebration by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra honoured Chinese culture through music and dance. Led by conductor Carolyn Kuan and host Dashan, the evening featured renowned pipa virtuoso Wu Man, pianist Ryan Huang, and a lineup of captivating programmes.