Chris Ong: A Keeper of Living Heritage 古宅古物故人情

English 英: Deirdre Kelly · Chinese 中: Translated by Ophelie C.

Photography: Nicky Almasy, GTHH

As Featured in 2025 Fête Chinoise Design Annual

Cover story of the 2025 Design Annual: Chris Ong’s impressive and richly storied Peranakan porcelain and historic objects, the largest private collection in the world, interpreted through our art cover.

The courtyard at Seven Terraces. Photography: GTHH.

The light in Seven Terraces filters gently through antique shutters, casting patterns on blackwood furniture polished to a soft gleam. Porcelain kamchengs sit proudly on sideboards, their intricate designs hinting at stories of a bygone era. For Chris Ong, this isn’t just a hotel—it’s a living archive of Peranakan culture, a legacy he fears could fade without care. “Heritage isn’t just about things,” he says, his voice steady but reflective. “It’s about stories, traditions, people—that’s what keeps it alive.”

Ong is no ordinary hotelier. Over the past two decades, the Penang-born former investment banker has transformed neglected shophouses and crumbling mansions into boutique hotels that double as cultural landmarks. His work has earned him accolades and admirers—but for Ong, restoring buildings is only part of the story. The real challenge lies in reviving what can’t be seen: rituals, values, and connections that give those spaces life.

走進檳城核心古蹟區充滿娘惹風情的 「七間老厝」(Seven Terraces),猶如走進時光隧道:古雅的花崗岩地板、黑木和珍珠母鑲嵌的傢俱、鍍金的櫃子椅桌、古雅又色彩艷麗的瓷罐、傳統娘惹婚床⋯⋯映入眼簾的一切,引領訪客一步一步回到清末民初的殖民地時代,沉澱在昔日土生華人大戶人家的氣派與輝煌氛圍。

Born into a fifth-generation Baba Nyonya family in George Town, Ong grew up in a household where tradition seemed to teeter on the edge of extinction. His parents embraced modernity, collecting Scandinavian furniture, which left their home devoid of the cultural relics that defined Peranakan identity—a unique blend of Chinese and Malay influences shaped over centuries in Southeast Asia. This cultural heritage was something Ong’s grandmother kept alive through stories and artifacts.

These porcelain stackable food containers are from Chris' personal collection. Tingkats are traditionally used during Chinese New Year to serve special cookies, cakes and sweets to the visitors. Photography: Nicky Almasy

These decorative pieces were hung on the wedding bed to bless the couple with good fortune and fertility. Photography: Nicky Almasy

An aerial shot of the living room of Stewart Apartment 2 at Seven Terraces. The rooms are decorated with a mixture of Antiques and modern furniture, including Walter Nichols rugs.Photography: Nicky Almasy

“She moved in with us when I was four or five,” Ong recalls. “She only brought what she could carry—two suitcases, a pair of blackwood benches, and some porcelain. My mother didn’t want anything else.” Those few objects became talismans for Ong, sparking an obsession that would define his life.

By his teenage years, he was spending all his pocket money on antiques—porcelain kamchengs (covered jars), tingkats (tiffin carriers), and sweetmeat trays that once graced Peranakan households. “I had unusual interests,” he admits with a laugh. Even when he moved to Australia in the 1970s and 80s for his career as an investment banker, he travelled with a small collection of these pieces. “I always kept them with me,” he says.

觸摸得到的古董藏品

在這裏,古董不再是可望而不可即,訪客可以在黑木雕花古董床上做個好夢,也可以在昔日大戶人家商議大事的古木餐桌上大快朵頤——桌上還擺放著價值連城的古瓷罐,不單是看得到,更是觸摸得到的文化熱情!這就是「七間老厝」掌舵人Chris Ong 獨特無私的保育理念:「古董不應放在博物館的玻璃裏,應該和我們一起生活⋯⋯文化遺產不只是物件,還有背後的故事、傳統和人情,這才是文化傳承的價值。」

能對訪客如此大方信任,大概源自他對古建築和古董的一份熱情。這份著重人與人的連繫,早於童年植根,關鍵人物是嫲嫲。生於第五代峇峇娘惹家庭的他,憶起嫲嫲時立即變得像個孩子似的:「嫲嫲在我四、五歲時搬進來,我媽媽不讓她保留其他東西。她就只帶著兩個行李箱、一對黑木長椅和幾件瓷器。」這幾件屬於嫲嫲的信物,開啟了其古董收藏的大門,即使七、八十年代隻身遠赴澳洲時,他亦隨身帶有藏品,決不忘根。

These porcelain stackable food containers are from Chris Ong’s personal collection. Tingkats are traditionally used during Chinese New Year to serve special cookies, cakes and sweets to the visitors. Photography: Nicky Almasy.

It wasn’t until decades later—after a successful career as an investment banker—that Ong returned to Penang. In 2007, at age 48, he found George Town on the cusp of being inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site—a recognition that would bring both opportunities and challenges. Determined to protect the city’s unique character and cultural legacy, Ong saw an opportunity to breathe new life into its neglected heritage buildings.

His first project was Clove Hall, an Anglo-Indian bungalow he restored into a boutique hotel before selling it for a substantial sum. With the proceeds, he began acquiring more properties: Muntri Mews, Seven Terraces, Jawi Peranakan Mansion and Muntri Grove—each one an architectural gem with a storied past.

Seven Terraces, another of Ong’s celebrated projects, exemplifies his vision for preserving Penang’s heritage while making it accessible to future generations. Located on Stewart Lane in George Town’s UNESCO World Heritage Site, the property was once a row of seven 19th-century Anglo-Chinese terrace houses in a state of near ruin.

an installation for a heritage day exhibition in 2023. "Altars to the Gods" at Seven Terraces. Notice the use lotus plates and 18in pais of vases. Photography: Nick Almasy.

回鄉肩負保育工程

落葉始終歸根,即使於異地當上了出類拔萃的銀行家,Chris Ong 仍心繫土生土長的檳城。2007年得知喬治市將獲納入聯合國教科文組織世界遺產名錄之時,時年48歲的他決心回鄉,保育自己珍而重之的歷史文物和傳統。

中年轉跑道殊不容易,但他活出了更真摯的自己,首個項目丁香廳(Clove Hall)成功將英殖時代別具英印特色的別墅復修成精品酒店,引得四方遊人慕名而來。回顧過去廿載,他先後將馬車房(Muntri Mews)、滿德禮園(Muntri Grove)「七間古厝」(Seven Terraces)、爪夷峇峇娘惹大宅(Jawi Peranakan Mansion)等多間幾近淪為頹垣敗瓦的失修古厝,復修改建成全新文化地標,保育成就贏盡文人雅士稱譽。

When Ong acquired it in 2009, the buildings were missing roofs and had been vandalized over decades of neglect. By 2012, after a meticulous restoration, Seven Terraces reopened as a boutique hotel with 18 luxurious suites filled with Peranakan antiques from Ong’s personal collection. Today, guests — many of them tourists from Europe and Australia — sleep in beds carved from blackwood and dine on tables set with porcelain that once graced Penang’s wealthiest homes. “Antiques shouldn’t sit behind glass in museums,” Ong insists. “They should be lived with.”

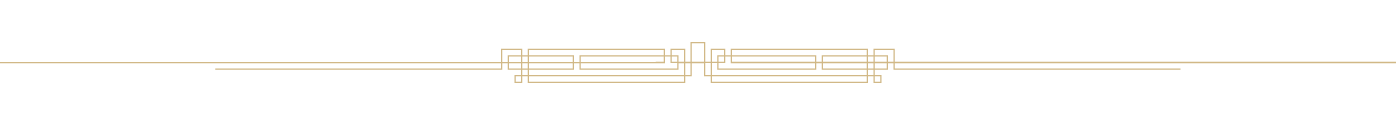

Chris Ong. Photography: GTHH.

“Antiques shouldn’t sit behind glass in museums. They should be lived with.”

Ee-Jeok are chair covers used to dress the chairs in the formal hall on special occasions like weddings, birthdays and Chinese New Year. This collection can be seen in all the rooms at Seven Terraces. Photography: Nick Almasy.

At his properties in George Town, Chinese festivals such as Pai Ti Kong (the Jade Emperor’s birthday) are celebrated with deep reverence, and guests are invited to take part. “We recently hosted a New Year celebration that incorporated traditional wedding bed hangings adorned with intricate embroidery and auspicious symbols,” Ong says. The textiles featured designs like fruits and birds representing fertility—details that link modern festivities to their historical roots.

“These rituals keep us connected to our ancestors,” Ong explains. He describes how today’s generation is reimagining these traditions, honoring not only their ancestors but even their pets. This evolution, driven by the temples, helps ensure that cultural practices remain vibrant and relevant for future generations.

Ong is acutely aware of how fragile cultural memory can be. He points to the 1949 founding of the People’s Republic of China as a turning point when much of China’s heritage was disrupted or destroyed—a legacy that rippled across diasporic communities such as Penang’s Chinese population. “Many people post-1949 don’t even know their culture,” he says. “What I’m doing is creating opportunities for them to reconnect.”

Through his work, Ong ensures that these rituals are not just preserved but reimagined, making them accessible to younger generations while staying true to their essence. For him, heritage is not static—it evolves, shaped by those who care enough to keep its stories alive.

A typical offering table for the ancestors. My family tradition calls for veneration at least three a year, Chinese New Year Eve, Ching Ming and 7th Lunar month. Photography: Nicky Almasy

Chris Ong 重視的始終是文化的連繫與傳承,保育古建築以外,旗下的喬治城物業在傳統節慶更籌辦各式各樣的節日慶典,例如春節初九慶祝天公誕辰,保留傳統之餘不忘注入新活力,「這些儀式讓大家慎終追遠﹐新一輩更將其現代化,不僅祭拜祖先,還會祭拜自己的寵物呢!」

如今他繼續保育檳城古天主堂,同時慷慨分享個人珍藏,2024年出版了個人收藏集後,更計劃將自家大宅改建成私人博物館。他興致勃勃地幻想著,要讓來賓坐在可招呼20人的英式餐桌上,欣賞每件古董收藏,體驗上世紀初清末民初的生活品味!

His dedication to preserving both tangible and intangible heritage inspired him to document his own collection in The Chris Ong Collection, a 270-page coffee table book published in 2024. Launched in November of that year as a limited-edition volume, it offers an intimate look at Ong’s Peranakan treasures—from intricate ceramic figurines to mother-of-pearl cabinets—how these objects were used in everyday life. Through its pages, readers are invited into Ong’s world, where every artifact tells a story and every piece of furniture holds memories waiting to be uncovered.

Blue and white fine china with a pattern from the Kangxi period used in a modern dining set up. Food is served in the miiddle in various covered bowls and small kamchengs. Photography: Nicky Almasy.

Despite his many achievements, Ong shows no signs of slowing down. After five years without new projects, he is now restoring a row of five arts-and-crafts-style buildings for Penang’s Catholic Church—a departure from his usual focus on Peranakan architecture but one he finds invigorating.

“These buildings have been empty for decades,” he says. “Post-COVID, everything is more expensive—from materials to manpower—but I’m excited because I’ve never done arts and crafts before.” The restored properties will serve as short-term rentals adjacent to Seven Terraces, blending functionality with historical preservation.

能令他對清末民初那個年代念念不忘的,是一位對他很重要的人。在訪問尾聲,他懷念嫲嫲之情溢於言表,「我猜我是想尋回那些嫲嫲失去了的東西。」語氣平靜的一句卻撼動人心,大概是這份血脈相承的親情大愛,給予他龐大力量守護屬於那個年代的一切。

This 12 inch mirror pair was scourced in Singapore and Vancouver and originally from the Penang family of Lim Kek Chuan. The cartouche is of the boroque bat design. The art on the body and cover is particullary fine and the interior has artwork of lively goldfish. Photography: Nicky Almasy

And then there’s his most personal project yet: transforming his own home into a living museum. The house—a pair of mirror-image buildings restored to reflect life from 1910 to 1920—is already filled with treasures from his collection. But Ong envisions something more intimate: curated dinners where guests can experience not just objects but the lifestyle they represent.

As up to 20 guests gather around his dining table—long and linear in British tradition—Ong delights in showcasing his collection of exquisite tableware and table art. From intricately carved utensils to porcelain pieces steeped in history, every item tells a story, turning each meal into a shared experience where connections are forged between generations and cultures alike. The table itself is symbolic: a meeting point where history is not only remembered but actively reimagined.

“I think it’s about trying to regain some of the things my grandmother lost,” he says quietly toward the end of our conversation. “Her not being here to see what I’ve achieved—or to hear her say, ‘You know, I think that’s enough’—is what drives me.”

These cylindrical Chinese teaspots come in a variety of sizes and colours, mostly utilitarian, it is rare to find these teapts that have not escaped the test of time. Photography: Nicky Almasy

In the skilled hands of Master Hui Ka Hung, paper transforms into vibrant, lifelike creations embodying Hong Kong’s cultural heritage.

Hong Kong is a fast-paced city filled with innovation and potential. Among its towering skyscrapers are streets alive with people rushing to their next destination. Beyond the urban chaos lie alleys steeped in history and tradition. It is here that artisans preserve Hong Kong’s cultural heritage through traditional skills passed down for generations. Among them is Master Hui Ka Hung, whose workshop, Hung C Lau, has become synonymous with the art of paper craft.