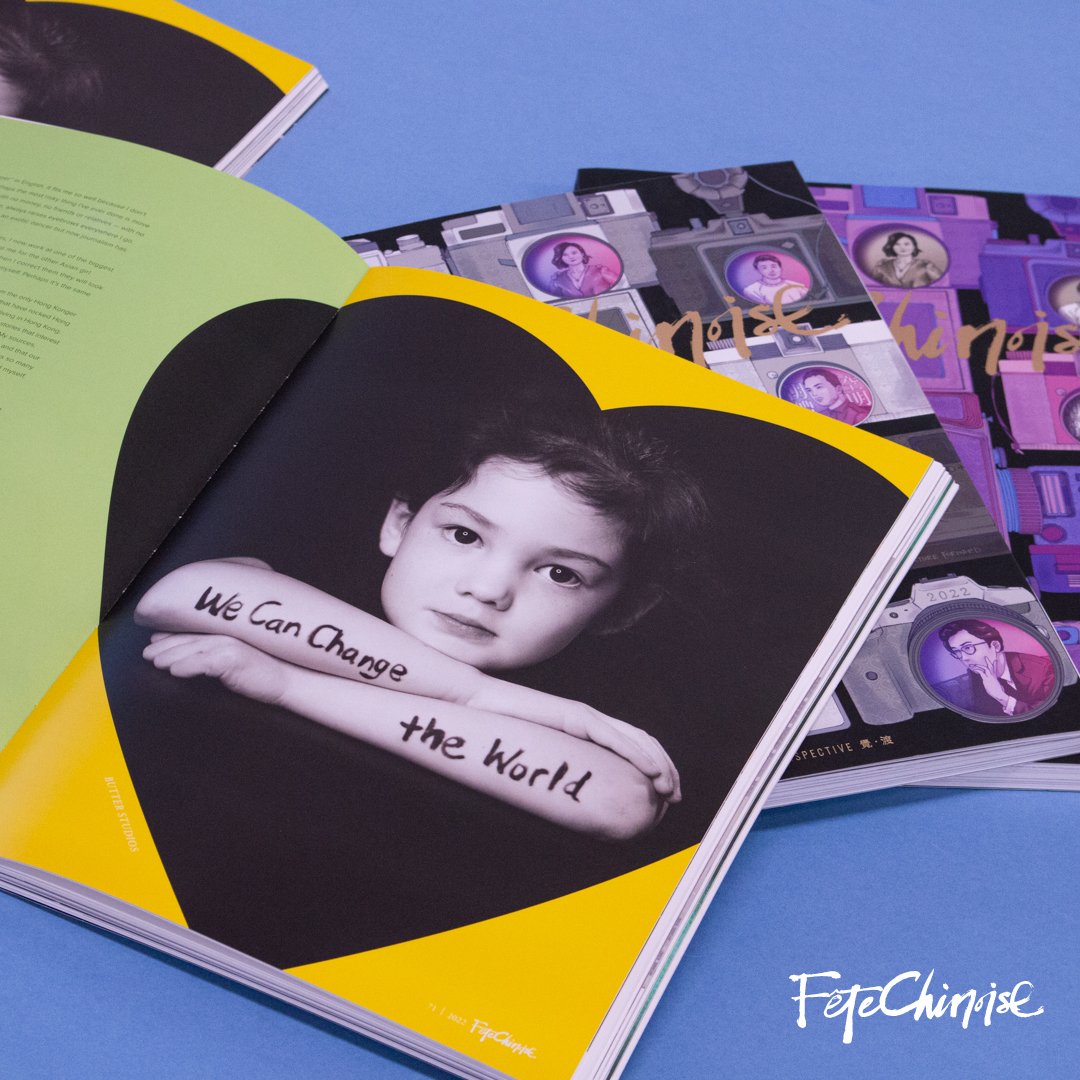

Conquering hate with art + Love 用愛與藝術征服仇恨 PART No.2

By Amelia Wong-Mersereau

rt reflects our ever-changing culture and has the ability to shift society's values and views. Racism and injustice have been a huge topics during the pandemic, magnified by the heartbreaking discovery of thousands of unmarked children’s graves at Indigenous residential school sites, the Black Lives Matter movement, and anti-Asian racism, discrimination and violence in North America.

This chapter is an artistic movement in response to the unwanted hatred. Read on as we embrace education, compassion, understanding, and love. The selections of words and images are from a pool of unique submissions from our readers.

藝術是文化變遷的倒影,也是改變社會價值點和觀點的領航。新冠疫情時,種族主義和不公正是一個重大的議題,從原住民寄宿學校令人心碎的數千個沒標記的兒童墳墓、「黑命關天」社會運動、到充斥北美的反亞裔主義、仇恨和暴力事件,令我們醒覺,面對那日益嚴峻的社會問題,我們不可以再繼續沈默。

此章就是我們的集體回應,是我們反仇恨的共同創造,一起以藝術對教育、共融、諒解和愛的擁抱。 你將欣賞到的文章及圖像,全是讀者們的原創作品。

“To conquer hate, we need to move those indifferent to Asian racism, because in silence, it grows. We need to be vigilant, take flight and educate. ”

Art by Helen Tran

Where are you from?

A place where incense swirls

Grasping at dancing words around me,

but hearing melodies instead

Each grain of rice a building block,

each slice of orange tightly wedging

the spaces of the

in-between where I exist.

Where am I from?

An ebony head of hair painted

every shade of the rainbow

Savagely stripped of its inkiness

Slowly letting the roots grow in,

like a topsy turvy tree.

Donët ask where Iím from, but where I am.

Standing face-to-face with

who Iím told to be

Seeing younger versions of myself

Gently ladling out traditions,

careful not to spill a drop.

poem by Jessica Gedge

art by Jenny Tieu

art by eva kwok

Both mercy and justice are appropriate and needed to confront racism.

Mercy is caring for those who have been crushed by racism.

We have to listen to their stories without interrupting.

We have to find a way to help them without sacrificing their dignity.

Justice is confronting the systems that build it up.

We have to stand up in the public square without violence.

We have to ban together to call out institutionalized practices that

favour one group over another

We need to act mercifully and justly.

Excerpt from a sermon on racism

Pastor Ho-Ming Tsui

art by penny lam

牡丹花中王,

Peonies - the Queen of Flowers in China

異國未覺香。

Grew in the beautiful garden on a foreign land

但憐秋霜影,

They were so resilient that they came back to life the next spring

來年艷驚芳。

And became the most stunning flower in the garden

Claiming My Space

Written by Citizenship Judge Albert Wong

A friend asked recently if I had experienced racism during my career in the Canadian military. My immediate answer, the same answer I gave throughout my 39-year career in the military, was “No, I was treated equally, the same as everyone else.”

It was a question spurred by the rise of anti-Asian racism fuelled by the COVID-19 pandemic. The questioner and I had started naval officer training together and he had the impression I fit in well back in 1978 and that I worked hard, giving my all. But given the current environment, he thought he should ask and apologized for not asking earlier.

I am of Chinese descent, born in Malaysia, emigrated to Canada, a Canadian citizen, had a lengthy and interesting career in the Canadian military, and am now serving as a Citizenship Judge. I am a partner, a father, a grandfather, a friend, a colleague. Successful, yet, I always felt I was a chameleon. My strength was to be able to adapt, blend in, stay into the background. I existed respectfully in someone else’s space – the perfect model minority.

So – where do I feel comfortable?

My friend’s question caused me to reflect back over the five decades of my life in Canada and I realized that I was always challenged on whether I was the right person for the job after each significant appointment was announced. I found out (years later) that many of my trainers thought I would be the first to fail my basic training. At almost every selection, someone from within my team would step up to question publicly why I was selected and not them, asking for the selection be overturned. At times, my challenger would find willing supporters and it would take the personal intervention of a more superior authority to stop me from being replaced.

Each time I shrugged off the challenge. After all, I was still on the job, better to work hard, tuck my chin down, and not draw too much attention to myself. It was more important to get the job done than draw unwanted attention by seeking credit. The perfect chameleon.

But now, thanks to the heightened awareness of anti-Asian racism, I have come to realize that I do have space, and more importantly, my space expands as others join in. Regardless of skin tone, gender, orientation, class, etc., everyone is welcome into my space. I also realized that my space would be a place for my granddaughters to grow and thrive.

Within my space where memories – happy and sad, pleasant and unpleasant —

are kept. I can visit these memories whenever I want to as they are not buried. My space also holds my culture.

And now, whenever I am challenged, my response will come from this space. Simply put, I don’t have to be ashamed of my skin tone, my accent, my thoughts, my culture.

This is a space of joy.

Personal Essay by Candy Chan

My Chinese name 善宜 means “kind-hearted” and “proper” in English. It fits me so well because I don't usually step over the line or do anything outrageous. Perhaps the most risky thing I've ever done is move to a strange city all by myself for a career in journalism — with no money, no friends or relatives — with no support system whatsoever. My English name Candy, however, always raises eyebrows everywhere I go. I sometimes joke to my Caucasian coworkers that I aspire to be an exotic dancer but now journalism has ruined me. It is a great conversation starter.

After a decade of producing diversity programs in multiple languages, I now work at one of the biggest mainstream newsrooms in Canada. Often my colleagues would mistake me for the other Asian girl working in the same building, call me by her name, or her mine. Often when I correct them they will look embarrassed enough for me to just laugh it off. It’s an honest mistake, I told myself. Perhaps it’s the same way we wear our hair.

We are so different, the other girl and I. She is Korean for crying out loud! In fact, I am the only Hong Konger in the whole newsroom. I would carry on pitching stories on anti-government protests that have rocked Hong Kong for months, or the National security law that would impact thousands of Canadians living in Hong Kong. Even though some of them may not see the light of day, as they are often being bumped by stories that interest Canadians more. It is the reality of the industry, I told myself, but it wasn't without frustration. My sources, my relatives, my friends in Hong Kong would remind me how important the Hong Kong story is, and that our voices need to be heard. Yet I must accommodate. Television news is a giant beast that involves so many moving parts where a single voice from one group may not be enough to draw an audience, I told myself.

Sometimes I feel sorry for that single voice. My voice.

I am one of the 1.5 generation immigrants. Those who emigrate to a foreign country as children and adolescents. Those who carry distinct memories and understanding of their motherland, while assimilating to their new country in every way better than their parents. Unlike our parents or second generation immigrants (“Banana” as we would call them, yellow on the outside white on the inside) — I am always aware of my uniqueness — the fact that I am split between two worlds. My relationship with my birthplace frozen in time. My identities are split cleanly into two. Feeling like an outcast, neither here nor there.

Even when given a platform, I am not sure my voice is worth being heard.

When I think of my parents and everything they've given me, I think of the hopes and dreams they once had for me. I think of the disappointments and frustrations they had to experience moving to a whole new country with me. I think of the distance I created between us so that we can tolerate each other better, while missing them more than I could express. Is it worth it, building everything from scratch? Holding on to what you believe in when you are so ready to give it all up? Is it worth it, seeing yourself questioning everything you do?

But I am also a witness to my family's assimilation. Time and again, I am reminded of my role within the Chinese-Canadian diasporas. The memories, values, languages and other things that we easily hide in order to become the model minority, are actually what make me unique. Even with constant self doubt and confusion I am the bridge and the interpreter.

I can tell you now mistaking one Asian for another makes one feel invisible and that is not okay.

I can tell you my name is part of my heritage and that my representation as a Hong Konger MATTERS.

I can tell you — my struggle is not my weakness.

sponsored by ferris wheel press.

The 2026 Signature Event Silent Auction is now live! Whether you’re attending the Signature Event or joining us in spirit from afar, everyone is welcome to place a bid. Discover an exciting selection of prizes, including luxurious hotel stays, access to captivating performances, exclusive hospitality packages, art collectibles, beauty and fashion items, and exceptional culinary experiences.

Proceeds from the Silent Auction will support the Fête Chinoise Cultural Foundation, Chinese Canadian Museum (Vancouver), and the Scarborough Health Network Birchmount Tower.